Before I left Indonesia, I made a promise that I leave with a kenangan — as a gift to remind myself how the country transformed me. A week before my departure, I interviewed Eko Cahyono, the founder of Perpustakaan Anak Bangsa, and the man who I happened to meet sometime in 2016 at a Toastmasters meeting. My name is Eko, he said, and I have a library. “You should come and visit.” I did — and discovered his story.

This piece was first published on Rappler Indonesia

BEYOND THE RIVERS OF SUKOPURO, in a house built of bricks and stones, a marriage is falling apart. Her husband of 12 years is off to find a new wife — a woman whose womb could continue a lineage.

One morning, in an attempt to distract herself from reality, she leafs through the pages of a book she plucked from a shelf. She wipes her wet cheeks, yet already a fresh stream of tears water the table.

“Mbak Mina,” a familiar voice asks, “why do you weep?”

“My husband is filing a divorce.”

The year is 2003 in Indonesia, and the country is in a ruckus. A series of bomb blasts rock a hotel and an airport in Jakarta. A peace negotiation between the government and Free Aceh Movement collapsed. Meanwhile, a librarian in a small village on the eastern part of Java is baffled: how can he appease a woman at fault for a childless marriage?

Suddenly, Eko’s phone rings, and Mina is left in midair.

The woman speaking on the other line is giving out her back issues of Femina magazine. “There’s 400 of them at home,” she says. “Please take them.” She’s leaving for Surabaya, and the magazines had to go — to someone else’s hands, or to the junk.

He looks at Mina, and tells her to wait. “Someone wants to donate Femina, your favourite read.” He hops on his motorcycle, and the engine revs. The woman lives in Malang City, some 15 kilometres away from Sukopuro, a village in Jabung in the regency of Malang, in between fields of sugar cane and rice paddies.

A couple of hours later, he returns to the library. He shows Mina the magazines that came in a sack. He leaves the second time to take the remaining loot. He would never find her again, except for a note she left on his table

Eko,

I am borrowing four copies of Femina. If my plan to fly to Hong Kong to work as a domestic pushes through, I will have my neighbour return these on my behalf.

Mina

It’s one of those days where he wished there are more things he’s capable of doing, like casting spells on a barren womb, so women didn’t have to live at fault for a marriage that failed.

“But who am I?” he utters in silence. “I’m just a librarian”

His name is Eko Cahyono. To many he is called Mas Eko, a Javanese term of respect towards older men. To others, they call him a recognition-seeker, a freak whose life swirl around piles of papers. To some, a curator of lewd literature.

“At the village,” he once said, “people don’t have much to do but sit idly and chat.”

It was that culture that he wishes to break.

THE DAYS of 1998 meander. The leather factory where he works shut down in the wake of a financial crisis. And then jobs became hard to find. To relieve himself from a tormenting repetitive cycle of days, he read all what he could find at home.

One day at the village, he meets an old man scanning through the words printed on a newspaper. The man was reading — upside down. It was in that moment he felt a fire in his belly, and soon his house is transformed into into a public space. At their terrace, he would hang magazines and tabloids on a clothesline. At night when they weren’t reading, they sang. Sometimes, they would discuss about public matters. Right in his family’s house, a library was born.

On some days he would knock on doors. And when a door opens, he smiles at the eyes that emerge from it. “Would you like to donate books?” It was a script that didn’t take a long time to master, except that he had to say repeat such line from one house to another, so they who came will always have something new to read.

He was Nuh and the library was his ship. He moved more than 10 times, until finally a neighbour offered a perfect deal: an empty land beside a peaceful graveyard – for rent. In 2008, there it was, a library built of bamboo and asbestos. He named it Perpustakaan Anak Bangsa, the library of the nation’s child. At the entrance, a pole stands with a flag on top, the emblem of their land.

They came and read, and he takes care of the rest. For a time, together with his sisters, they would sell coffee, cigarettes, and gorengan to pay for electricity. Later his sisters would begin their own families, and he would be on his own. He wrote stories and sold them to newspapers. He manned book fairs. He earned commissions from loan referrals. He did all sorts of jobs to pay the rent. And when they weren’t enough, he sold what he had: his television and a motorycle.

One stormy night, a tree falls and violently crashes the library’s roof. The next morning, he knew something had to be sold again.

Perhaps, he thought, “I could sell one of my kidneys.”

NOBODY IN THE VILLAGE, not even his parents, thought of the idea that an erstwhile factory worker and a high school graduate would become a librarian.

Those who frequently visit fondly call him mas, and loved him dearly. But others thought he was a joke, others called him sok cari nama, or someone who just wanted to gain popularity. They belittled him and talked at his back. Once, police came after they caught wind that he was harboring pornography at the library, even if it were just magazines that tread on sexuality and reproductive health, even if it were just a pile of Femina, a favourite among housewives who felt empowered for reading it.

So when the police who came finding no evidence, they ended up borrowing books.

Here is a library, where readers find company and answer to uneasy questions, like how does a 12-year-old student cope with life when the head of his family, the one who’s supporting them, is only given 6 months to live?

This was the story of Tema, who few years ago run into Eko for advise. He was contemplating of quitting school — even if he were only months away from graduation. His father’s diabetes has affected his nervous system. An operation had to be performed on top of expensive medications. Someone had to pay the bills, and at that young age Tema felt it had to be him.

“Seandainya aku ini orang sakti.” If only I were a man of supernatural powers, Eko said in a thick Javanese accent.

But what can a librarian do?

He tucked books inside his bag. The books were about reflexology, another about ancestral heritage, and the other on traditional medicine. Seven months later, he returned, wearing a high school uniform. It was those books that he lend Tema that gave his father a new lease of life.

Beyond the rivers of Sukopuro, there is a library – and it’s evidently more than that.

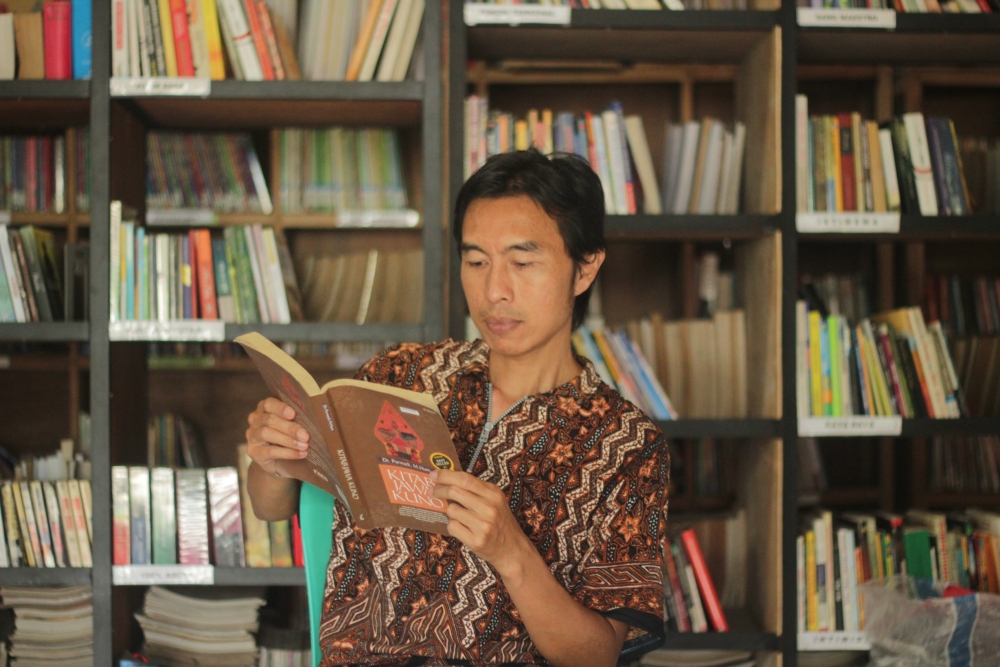

JULY 2017. FEW DAYS AFTER LEBARAN. As I came to visit the library to capture the librarian’s life in photographs, a 16-year-old walks into the library. He grabs Eko’s right hand. Gently he presses it into his forehead. He moves to my direction and does the same to mine. He asks whether it’s alright to come in. It’s fine, Eko tells him. He dashes into the comics section, and Eko returns to his table.

“That’s Arif. He stays at a pesantren nearby,” Eko tells me, “so when he’s free, he comes here to take a break from school-related readings. Some fifteen minutes later, the boy, clad in apple green sweatshirt, is one with silence. As he nestles behind a towering bookshelf, a book transports his mind into another world.

On Eko’s table are piles of books, a plate full of rice cake wrapped in banana leaves, some drinking water in plastic cups, nuts and spicy rice chips stored in glass jars.

Another visitor emerges from the doorway. He lifts the tarpaulin, the only material that’s covering it. He shakes our hands, and later asks Mas Eko for Aloe Vera leaves. “That’s another regular visitor, they have livestock at home,” he tells me. Later, he extends his arm for another round of handshakes. He couldn’t stay longer, he says, and lifts the tarpaulin cover. “Salamualaikum.”

The books, tens of thousands of them stored inside this 72-square-metre space, are left unguarded, and it’s meant to be that, Eko says, so people can come and borrow whatever they want. Unlike many libraries, the only rule here is to read.

When UNESCO study revealed that in Indonesia, only 1 out of 1000 people read a book per year, he was one of those who raised an eyebrow: who says Indonesians don’t read?

“At the library the least number of people who come here every day hovers at 50,” he said.

“Indonesians like to read, if they’re given convenient access to libraries. They read, if libraries allow them to read any time of the day, without the usual bureaucracy of requiring them to photocopy their KTP, pay administration fees, and fine them when they couldn’t return the book in a week.”.

Outside the library, a giant mango tree’s shadow falls on a grove of purple boat lilies and snake plants that spiraled from the earth, as if triggered by a recording of a sindhen singer blaring from neighbour’s stereo. There are herbs planted in pots made from cut plastic bottles. A goat bleats, taking turns with the crowing cocks while they scratch their bamboo cages. The smell of burning wood under a boiling pot of rice wafts the air.

It was in 2011 when the library was finally reconstructed into a concrete hall, through the help of donors. And since then, it sits on land it rightfully belongs. On its wall, I see picture frames, medals, and trophies chronicle the history of a library with a whopping 8,000 membership. They are students, factory workers, teachers, and household wives that come here to read from a collection classified in the whims of the librarian: wow memukau (awakening), petunjuk hidup (guide to life), superpower, khusus kutu buku (exclusive for bookworms), super hot, kontroversi (controversies), among others.

They read and borrow, and return the books at their own pace. Yet the books have always found their way back. “I’d like to think that the books are just out there travelling with their readers,” he once told Andy Noya, a celebrated TV host in the country.

Among those on ‘travel’ list is Laskar Pelangi, a fictional story of young students on Belitung island in Sumatra, where the kids and their teachers struggle to keep a lone elementary school in the village running, a familiar story not far different from the library’s: that sometimes, noble acts of kindness arise from those who barely have anything.

The book was away for a good three years beginning in 2006, passing from one hand to another. So in 2008, Andy pledged to give the library 25 copies of it. Another 25 of Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, and another for dictionaries. The meek librarian tried his best to contain his happiness as a thunder of applause drowns the studio. It was a moment well-kept in pictures that hang on the wall. Another frame describes Eko as a hero. Beside is a picture of him with President Joko Widodo taken at the Palace in April. At the time the president invited community librarians around the country to discuss what their needs are. On that day, Jokowi promised to ship 10,000 copies of books to each of them. To make it easy for those who support community libraries, the president asked state-owned Pos Indonesia to make shipping free for those who sent books to libraries every 17th of the month.

I asked Eko what’s in his mind as he looks back all the memories that built Perpustakaan Anak Bangsa. “Biasa aja mas,” he tells me. Nothing extraordinary, an expression that embodies self-restraint. That when you’re doing something for the people, do it without putting things into your head.

This is a story of a man who devoted some good twenty years of his life to a noble cause. Fueling people’s interest towards reading through a village library he built in 1998 is a story truly filled with altruism. To ensure people have something to read, says Eko, is a responsibility. His responsibility.

What motivates him to do all these? Now 37, Eko evaded the question, and instead returns to the stories that built the library.

ONE MORNING IN 2007, while attending to the scores of books that gathered dust and webs, a white Toyota Innova parks in front of his house few steps away from the library. He runs out to find out who it was. The door opens, and a woman in high-heels alights. She asks him where the library is. She must be a donor, he thought.

“How are you, Mas Eko?” the woman in beige dress and crimson red skirt grins. She takes off her sunglasses.

“It’s me, Mina.”

For all those times there had been no news about her, he wondered how her life has been, her divorce and her life in Hong Kong.

Do you remember those magazines I borrowed, Mas Eko? She asked. She read them all. It was those pieces of hand-me-downs that taught her how to improve her fertility. Those magazines that once became a piece of controversy, that jeopardized a library — saved a marriage. Her husband retracted a divorce petition on the day Mina’s doctor found life in her womb. She gave birth to twins.

And the air is filled with solace. There was no need for him to possess super powers. To be a librarian—it was more than enough to transform lives.

Few minutes before I wrapped up the day of interviewing Eko, I studied those amiable almond eyes that returned to the pile of books on the table. “These are new donations up for inventory,” he tells me. The azhan reverberates in the air, and the rays of the afternoon sun beam through a tall glass window — forming a circle of light around his head. It was a glimpse of a day in life of the man they call Mas Eko. But perhaps — beyond the rivers of Sukopuro — a village that is home to where children, housewives, labourers, people from all walks of life could educate themselves through the books they read, there is a term that fits him even more: the people’s librarian. ◊